Supporting People with Complex Needs and Specific Conditions

Scope of this chapter

Certain conditions can lead to a person’s needs being more complex.

For example:

- Acquired brain injuries;

- Cancers;

- Dementias;

- Epilepsy;

- Schizophrenia;

- Severe Learning Disability;

- Stroke.

Complex needs may be life-long, or only last a short period. For example, whilst a person is recovering from illness.

Complex needs generally fall into one of 4 categories of need, although often people with complex needs will have needs across more than one area:

- Physical;

- Mental health;

- Behavioural;

- Communication.

This chapter provides guidance about working with people that have complex physical, mental health, behavioural or communication needs. It also offers guidance for some specific conditions - Autism, Dementia, Cancers, Parkinson’s Disease and PMLD. The focus is on providing safe care and treatment, promoting independence and maximising choice and control.

Relevant Regulations

Related Chapters and Guidance

- Accidents, Injury and Incidents

- Ageing, Illness and Dying

- Choice and Control

- Communicating Effectively

- Dignity and Respect

- Everyday Healthcare

- Participation and Advocacy

- Partnership Working

- Personal Safety and Wellbeing

- Promoting Independence and Strengths

- Safe Care and Treatment

- Safeguarding and Deprivation of Liberty

Amendment

In May 2024, information about delegated healthcare activities was moved to the chapter Everyday Healthcare.

Physical needs are health related needs. They occur when someone has a health need that requires specialist care, support, or treatment to reduce the risk of health deterioration.

For example:

- Risk of (or actual) pressure areas;

- Stoma;

- PEG tube;

- Tracheotomy;

- Double incontinence;

- Immobility or severe mobility needs;

- Oxygen dependency;

- Dysphagia (elevated risk of choking or aspiration);

- Any condition that is deteriorating rapidly or that fluctuates significantly.

Skilled medical support and care is needed for people with complex physical needs.

Many people live with severe and enduring mental health issues.

For example:

- Eating disorders;

- Obsessive compulsive disorders (including hoarding);

- Self-harming behaviours;

- Drug and alcohol addictions;

- Depression;

- Schizophrenia;

- Bi-Polar Disorder.

If these are stable and managed, they are not complex. Mental health needs only become complex if they are unmanaged, unstable or fluctuating unpredictably.

Anyone with a complex mental health need should be in receipt of specialist support and treatment from a community mental health service. This is normally a Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) consisting of a Clinical Psychiatrist, Clinical Psychologist, Community Psychiatric Nurses and Healthcare Assistants.

If for some reason a person being supported is not being supported by a mental health team, take steps to enable them to access it. The referral to a mental health service can only normally be made by a GP, so this may involve contacting the person’s GP on their behalf (subject to normal consent rules).

A mental health professional should:

- Support the service to understand risks and develop strategies;

- Make sure staff know how to recognise a deterioration in mental health;

- Make sure staff know when to seek emergency intervention and when to contact the CMHT;

- Be available to provide advice and support to staff as needed.

Any instructions given by mental health professionals should always be followed. Changes should not be made without their agreement.

The NHS website can help locate an emergency 24hour mental health advice service in the local area.

If the person appears to have rapidly deteriorating mental health needs, their community mental health team should be contacted as a matter of urgency. They can arrange to visit the person, assess needs and amend treatment as necessary.

However, if the person needs immediate support with their mental health do not wait for the community mental health team to be available. Call 999 and explain what is happening. This will enable the right emergency service to be dispatched.

Police

If the person is at an immediate risk of harm, or of hurting others, the police will normally attend and remove them to a place of safety. Once safe, an Approved Mental Health Professional (AMHP) can carry out an assessment under the Mental Health Act 1983 to determine whether they should be admitted to a mental health hospital (sectioned).

Sometimes, the police will work jointly with a local mental health service and attend with a mental health nurse to try and avoid the need to remove the person or section them. Instead, the mental health nurse will try to take steps to manage the risk and de-escalate the situation. Once the immediate risk is reduced, the person can then be supported by the community mental health team.

Paramedics

If the risk of harm is not immediate, paramedics will normally attend. This can result in the person being taken to A & E, where their mental health needs can be formally assessed by an AMHP. Most A & E departments have direct links to the AMHP service to make these arrangements.

Behaviour is a way of acting. It is something we all do.

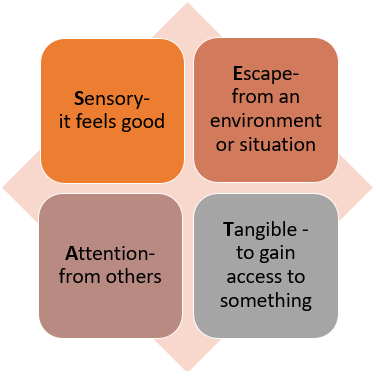

Behaviour serves one of four functions, described as SEAT:

Behaviour becomes complex when it is frequently challenging, unpredictable, unmanageable, or poses a risk of harm to the person or to others.

The first thing to remember is that complex behaviour does not just happen. There is always a reason for behaviour, although not always an obvious one.

It can take time to understand the trigger and may need the involvement of a specialist, such as a Clinical Psychologist or a Speech and Language Therapist.

The first thing to check is that all the person’s care and support needs are being met as per their individual care or support plan. Unmet needs can lead to complex behaviour triggered by things like hunger, thirst, discomfort, boredom, poor communication etc.

Complex behaviour may be a response to physical pain or illness. If it is not clear what may be triggering the behaviour, steps should be taken to contact the person’s GP as soon as possible so that illness can be ruled out (or treated).

To support a person with complex behaviour, it is essential to understand the cause or causes. This normally involves using an ABC chart to record each incident.

ABC stands for Antecedent-Behaviour-Consequence.

Antecedent: What was happening just before the behaviour?

Behaviour: What was the behaviour that occurred?

Consequence: What happened as a result of the behaviour?

Recording the behaviour enables patterns to emerge:

- Specific triggers, such as the actions or presence of a particular individual or potential side effect of medication;

- Any wider triggers, such as being hungry, tired or bored;

- Environmental factors, such as a TV programme, music;

- The situations when the behaviour is most likely;

- Staff approaches that reduce or intensify the behaviour;

- The function that the behaviour is serving (SEAT).

ABC chart evidence should be used to develop a behaviour support plan. Depending on the level of risk to the person or others, a Clinical Psychologist may be best placed to develop the plan after reviewing the recorded evidence.

For further information about behaviour support plans and complex behaviours, see:

The Challenging Behaviour Foundation: Positive behaviour support planning

Rule number one is 'stay calm'. Any panic or extreme reactions by staff can quickly escalate complex behaviours or upset other people in the vicinity.

If there is a behaviour support plan in place, the strategies in the plan should be implemented.

If there is no behaviour support plan (or the strategies in the plan are not working), the response should be very much determined by the individual triggers that the person is known to have. You do not want to make the situation worse by responding in a way that will increase anxiety, anger etc.

Remember, the most important thing is always to keep people being supported as safe from harm as possible.

Non-physical intervention

Non-physical interventions are ‘hands-off’ interventions.

Some things to try may include:

- Positive language - do not ‘tell someone off’ or reprimand them;

- If the person is upset, they may find appropriate touch calming and reassuring;

- Offer positive activities and experiences as a distraction;

- Play calming music;

- Offer a drink or something to eat;

- Use humour if appropriate, but make sure the person does not think you find their frustration funny or are laughing at them;

- Support other people in the area to move to a safer space.

Physical interventions

Physical interventions are ‘hands-on’ interventions.

Physical interventions should never be planned to take place in advance. They should only take place when non-physical interventions have not worked and a failure to intervene would leave the person or others at a high risk of harm.

The level of physical intervention used should be the least restrictive possible, and never more than is necessary to keep people safe.

During a physical intervention staff must do everything possible to prevent injury or distress and to maintain the person’s dignity and privacy.

Physical interventions should not be used routinely.

If the use of physical intervention increases, expert advice from a Clinical Psychologist should be sought to develop or review a behaviour support plan.

PRN anti-psychotic medication and restraint should only ever be used as a last resort when there is no other way to keep people safe.

Neither PRN medication nor restraint should be used routinely to manage or prevent complex behaviour.

This is a severe deprivation of liberty.

If the use of PRN medication or restraint increases, expert advice from a Clinical Psychologist should be sought to develop or review a behaviour support plan.

Risks around complex behaviour should be assessed in the same way as other risks.

See: Risk Assessment (person-centred)

If incidents of complex behaviour cause any harm to the person or to others, they must be recorded, reported and investigated in line with relevant processes.

See: Accidents, Injuries and Incidents

If the incident or injury occurred or could have occurred as a result of abuse or neglect a safeguarding concern should be raised to the local authority.

Complex communication needs happen when there is a difference between the way that we communicate and the way that a person being supported communicates.

It is a problem for the person but is not their problem to resolve. It is ours. If we do not resolve it, we cannot provide care and support that is person-centred or safe. We cannot maximise participation, choice, and control. We may not know if someone is frustrated, upset or in pain.

Language barriers exist when the person’s first language is not that used by staff.

Most people will have some understanding of English, but we should not expect them to communicate in English if it is not their preferred language.

Steps should be taken to allocate staff that speak someone's preferred language to their support team. This may require recruitment of staff.

Written information should be translated into people’s preferred language.

To maximise participation, people may need an interpreter or a family member to support them in any conversations about care or support planning, risk assessment and when making key decisions.

The above guidance also applies to people with a visual or hearing impairment.

If the barrier is not language itself the following are some techniques that everyone can try to adapt communication:

Presenting information in another way

- Using pictures e.g., of objects, feelings, or choices;

- Using easy read written information.

Objects of reference

An object of reference is a physical object that is relevant to the conversation or question.

For example, when asking if someone would like a cup of tea, show them a cup and a teabag so they know what you are asking.

For example, if the person wants something, can they take you to it and show you?

Ensuring sufficient time

Sometimes communication is ineffective simply because we do not have or allow enough time:

- To communicate what we are saying or asking in a way the person understands;

- For the person to think about their response;

- For the person to prepare what they want to communicate back to us;

- For the person to communicate in their preferred way.

This is a matter that must be raised and addressed, as it is not acceptable.

People that have extremely specific communication needs that impact on their quality of life should be supported to access a Speech and Language Therapy assessment.

A Speech and Language Therapist (SALT) can assess communication needs and develop a communication passport that can then be used by everyone to communicate more effectively.

A SALT can also work directly with the staff team to help them understand the person’s communication style, develop strategies for effective communication and use any specialist communication equipment they provide.

Examples of specialist equipment or techniques that a SALT may implement include:

- The TEACHH system;

- Makaton;

- A communication board/mat;

- Augmentative and Alternative communication, (AAC), devices, such as Voice Output Communication aids (VOC).

This section provides information about Autism, along with some tips and strategies for maximising the participation of people with Autism in care or support planning, risk assessment and everyday decision making and activities.

The Health and Care Act 2022 requires all health and social care service providers registered with the Care Quality Commission to provide employees with training on autism and learning disabilities appropriate to their role (called Oliver McGowan Training).

The training aims to provide the social care and health workforce with the right skills and knowledge to provide safe, compassionate, and informed care to autistic people and people with a learning disability.

For further information about the training and how to access it see: The Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training on Learning Disability and Autism.

Autism is caused by unusual brain development and is a lifelong condition.

There are core difficulties experienced by every person with Autism. However, the precise nature of those difficulties will be unique to the individual.

Autism can affect people across all levels of intelligence, and not all people with Autism have a learning disability or difficulty. For example, Asperger's Syndrome is a form of Autism that affects people who are average, or above average intelligence.

Autism can co-exist alongside conditions that can exacerbate difficulties and affect how well a person with Autism is able to develop and implement strategies and approaches that may be helpful to them.

Common conditions include:

- A learning disability;

- Dyslexia;

- Dyspraxia;

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD);

- Mental health issues.

Everyone with Autism shares some core difficulties with social communication, social interaction, restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour and sensory sensitivity.

Social communication

Social communication is the ability to interpret meaning behind one or more of the following:

- The spoken word;

- Tone of voice;

- Facial expressions;

- Jokes, sarcasm and hidden meanings.

Because of their difficulties with social communication, a person with Autism may:

- Not speak, or have limited speech;

- Use alternative means of communication (e.g., Makaton or behaviour);

- Find it hard to understand or use abstract concepts;

- Only talk about the same topics;

- Repeat what other people say.

Social interaction

Social interaction is the ability to ‘read’ other people and respond accordingly.

People with Autism can have difficulty:

- Predicting how other people may act, or want them to act;

- Understanding the feelings and emotions of others;

- Understanding concepts such as personal space, privacy and consent;

- Expressing their own feelings and emotions.

A person with Autism may:

- Withdraw from or avoid social interaction;

- Behave in ways that are not appropriate (e.g., touching without consent);

- Appear insensitive to the needs of others (e.g., laughing if someone is upset);

- Find it hard to form friendships, or develop inappropriate relationships;

- Express their own emotions inappropriately (e.g., through aggression or self-harm).

Repetitive behaviour and routines

People with Autism often become dependent on repetitive behaviour and routines. This provides stability and assurance but can lead to heightened anxiety when things change or do not go as planned.

Highly focused interests

Many people with Autism develop specific interests that they focus a lot of time and attention on. These interests can be very important to the person’s wellbeing, even if they do not make sense to anyone else.

Sensory sensitivity

Many people with Autism are hypersensitive and/or hypo sensitive to a range of things:

- Certain sounds and volume;

- Light;

- Touch;

- Temperature;

- Colours and patterns;

- Taste;

- Smell;

- Pain;

- Body awareness;

- Vestibular senses (balance).

If a person is hypersensitive to something they require much less exposure to it, and sometimes need to avoid it altogether. Too much exposure is normally very distracting and can cause significant anxiety, feelings of nausea and even physical pain.

If a person is hyposensitive to something they may seek it out or be desensitised to it altogether.

Peter is hypersensitive to bright light. At home he keeps his curtains drawn and when he goes out, he always wears sunglasses.

Susan is hyposensitive to pain and touch. She regularly bangs her head onto things if she is anxious as she finds this calming.

John has a hyposensitive vestibular system. He spends several hours a day rocking backwards and forwards and spinning around.

Moe is hyposensitive to sounds. He always has the TV on very loud, bangs doors and likes being in noisy places.

Sandy is hypersensitive to sound. She can hear conversations from a long way away and finds them very distracting as she cannot block them out. Loud noises become distorted and overwhelming.

Carol is hypersensitive to the texture of food in her mouth. She will only eat smooth food like mashed potato or ice cream.

Sandeep is hypersensitive to touch on her scalp. She finds it difficult to wash or brush her hair and experiences this as pain.

David has hyposensitive body awareness. He finds it hard to navigate a room and regularly bumps into objects and people.

There are a range of strategies that, depending on the nature of their difficulties, may help a person with Autism:

- To communicate with others;

- To understand the communication of others;

- To identify emotions in themselves and in others;

- To learn about appropriate social interaction in specific circumstances;

- To develop and manage routines;

- To adapt to change;

- To cope with feelings of anxiety and being overwhelmed;

- To identify risky situations;

- To learn to carry out everyday tasks independently.

These strategies are normally agreed with a Speech and Language specialist or a Clinical Psychologist, and it is important that anyone supporting a person with Autism can apply the approaches effectively. Examples include the use of social stories, visual aids and systems such as TEACCH.

The precise ways to maximise each Autistic person’s participation will be determined by their unique difficulties.

Staff should avoid making assumptions or generalisations about this and always take steps to find out the best way to maximise their involvement before proceeding.

The following table sets out some steps that should be considered in most circumstances:

| Step | Further information |

|---|---|

|

Limit disruption to normal routines |

Try to plan meetings outside of times when key routines take place, or if this cannot be avoided take breaks to allow a person to carry out a particular activity or task. The person may be reliant on their routines to provide stability to their day, without which they could become overwhelmed or anxious. |

|

Provide as much information, as early as possible and in as much detail as the person needs |

Provide information about the purpose of the meeting, the planned duration, the venue, the agenda, any planned breaks, who will be there, what will be discussed etc. Liaise with any other person who may be able to support the person to understand the information and prepare for any meeting. |

|

Stick to the plan above |

If you set expectations, make every effort to meet them. Any last-minute changes could damage rapport with the person and cause significant anxiety to the person. This includes lateness. |

|

Consider any support the person may need |

The person may benefit from the support of an advocate, friend or carer. This support may not only be needed during the meeting, but also beforehand to help the person prepare, or afterwards to help them talk through the meeting and next steps. |

|

Create the optimum environment |

Find out what is likely to cause distraction, anxiety or distress. Aim to create an environment that is as calm as possible. This could be literally anything and may not be obvious so don’t make assumptions. For example, a bright light, a ticking clock, a busy road outside, the clothes that you wear, the colour of the room, perfume, the smell of food cooking etc. |

|

Talk about the person’s specific interests |

Talking about the person’s specific interests can be reassuring and calming for them. It can also help build rapport and support the person to move on to talk with you about other things. |

|

Use the person’s name if you are speaking to them (e.g., Tom, can I ask you about….?) |

The person may also have difficulty filtering out background noise to focus on one particular voice. Using their name at the start of a sentence or question will help them focus. |

|

Break information down |

Too much information can quickly become overwhelming, so try to break things into manageable chunks. |

|

Communicate effectively |

Find out how the person normally communicates and try to replicate this. This could be through a storybook approach or using visual aids. Communication via text or email can work well for a person with Autism, as it allows them to communicate at a time that works best for them and avoids the need for face-to-face social interaction. |

|

Be literal |

Always speak literally to the person and to others present. Do not make jokes, use hidden meanings or ‘beat around the bush’. Avoid making jokes with other people who may be present when the person is there, as they may not understand why people are laughing and could become confused or upset. |

|

Don’t ask too many questions |

Answering questions can be difficult, because this involves social communication and interaction. Try to keep these to questions that are pertinent to the situation in hand. |

|

Allow time to digest information |

The person may need time to process information, and support to make sense of it and consider a response. |

|

Wellbeing checks |

The person may become overwhelmed, but because of difficulties with social communication and interaction this may not be obvious from their facial expressions or what they say. Offer opportunities to take a break, particularly if the meeting is long or the person is being provided with lots of information. |

This section provides information about cancer, along with some tips and strategies for maximising the participation of people with cancer in care or support planning, risk assessment and everyday decision making and activities.

Cancer is the medical term used to describe the abnormal and uncontrolled division and multiplication of cells in any part of the body. The result is a tumour that can directly impact how well the affected area of the body functions.

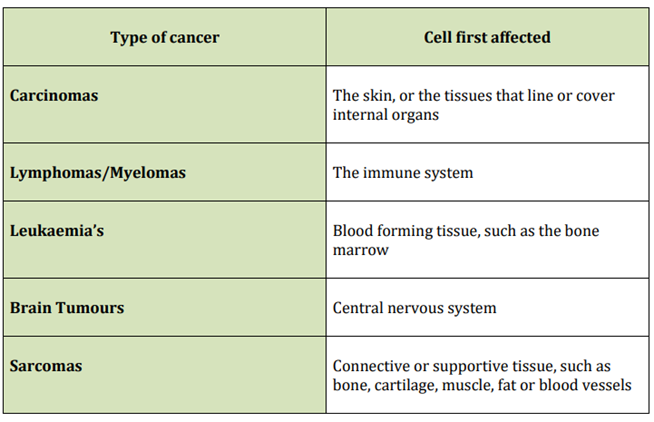

There are 5 main types of cancer:

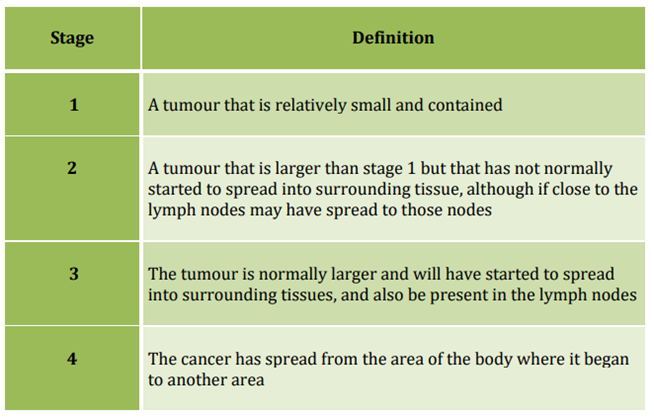

Cancer stages

Staging systems are used by health professionals to help them decide the best course of treatment.

There are 2 staging systems commonly used, but the number system set out below is the most widely recognised.

If a person has Stage 4 cancer, the first place that the cancer occurred is known as the ‘primary’ cancer, and other cancer sites are described as ‘secondary’ cancers.

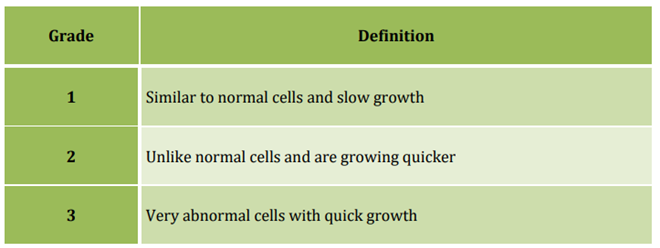

Cancer grades

As well as using a staging system, cancers are often graded based on how normal (or abnormal) the cells in the affected area are.

Generally, a lower grade indicates a better outlook, whereas a higher grade will normally require more urgent and intensive treatment.

Cancer treatments

There are a range of cancer treatments available. The treatment provided depends on the part of the body affected, the size of the tumour, how quickly the cancer is progressing and the general health of the person.

Examples include:

- Surgery to remove the affected organ or tissue;

- Chemotherapy;

- Radiotherapy;

- Cancer drugs;

- Hormone therapy;

- Bone marrow and stem cell transplants.

Many cancer treatments have side effects. Side effects will be specific to the treatment and the reaction of the person to that treatment, but can include:

- Fatigue (extreme and prolonged tiredness);

- General weakness;

- Breathlessness;

- Loss of appetite;

- Mood swings and depression;

- Numbness of the hands and feet;

- An increase in infections.

The physical impact of cancer and the side effects of treatment can make carrying out everyday tasks challenging.

Increased care and support needs could exist on the day that treatment is received, in the days following treatment or throughout an entire course of treatment and beyond.

There is no reason why a person with cancer cannot fully participate in planning and decision-making processes.

The following table demonstrates some of the steps that staff can take to facilitate this:

| Step | Further information |

|---|---|

|

Speak with a person in the optimum environment for them |

Feeling at ease facilitates involvement and increases the person’s sense of control. The person may associate certain places with a loss of choice and control, and these should be avoided wherever possible. |

|

Speak at a time that works best for the person |

Try to avoid times when the person is likely to be feeling unwell or tired following treatment. |

|

Make sure they are happy to proceed as planned above |

People with cancer can have good and bad days. This can be regarding their physical health but also their emotional resilience. If the person is having a ‘bad day’ postpone the conversation or offer an alternative way for them to provide the information you need. |

|

Avoid having lengthy conversations |

People with cancer can become tired quickly. They may prefer several short conversations, or an alternative means of providing information. |

|

Take regular breaks |

Even if the person with cancer is not experiencing physical fatigue, talking about their needs can be emotionally exhausting for them, and also for any carers. |

|

Consider any support the person may need |

The person may benefit from the support of an advocate, a friend or a health professional as well as any carer. This support may not be needed during a conversation but could be needed after it to support the person to talk through what has been said and next steps. |

|

Allow time for the person to talk about their worries and wellbeing, and show that you are listening |

The person is likely to have worries and concerns for the future. Recognising these concerns will build rapport, and also support the person to move on to talk about their current needs and outcomes in a positive way. |

This section provides information about Dementia, along with some tips and strategies for maximising the participation of people with dementia in care or support planning, risk assessment and everyday decision making and activities.

Dementia is a complex syndrome (a group of related symptoms) associated with an ongoing decline of the brain and its abilities, which diminishes the ability of the person to do everyday tasks over time.

Common symptoms of most Dementia include:

- Loss of memory;

- Difficulty in understanding people and finding the right words;

- Difficulty in completing simple tasks and solving minor problems;

- Mood changes and difficulties managing emotional responses.

Symptoms typically worsen as the condition progresses to more areas of the brain, and in later stages of Dementia a person may experience significant difficulties with all bodily functions, including mobility, swallowing, continence, and speech.

There are several types of Dementia that can be diagnosed, depending on the cause. The most common are:

- Alzheimer's Disease;

- Vascular Dementia;

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies;

- Frontotemporal Dementia.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is thought to affect around 520,000 people in the UK. During the course of the disease, the chemistry and structure of the brain changes gradually over time, leading to the death of more and more brain cells. Associated symptoms get progressively worse. There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease although symptoms in the earlier stages can sometimes be managed with medication to delay the progression of the condition.

Vascular Dementia

Vascular Dementia is the second most common type of Dementia with around 150,000 people affected. Vascular Dementia occurs when the brain cells die because they have been starved of oxygen. This can be following a Stroke but can also be caused by a blood clot or a disease of the blood vessels in the brain. Unlike Alzheimer’s Disease, Vascular Dementia symptoms suddenly worsen each time the brain is starved of oxygen and, depending on the area of the brain affected, the symptoms can be localised to the functions that particular area of the brain controls.

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Lewy Bodies are small deposits of protein that appear in nerve cells in the brain, causing the Dementia. Lewy Bodies are also associated with Parkinson’s Disease and people with Lewy Body Dementia may experience the symptoms of both conditions depending on whereabouts in the brain the Lewy Bodies are deposited. Hallucinations, delusions, and sleep problems are more common in people with Lewy Body Dementia than with other types of Dementia.

Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal Dementia (also known as Picks Disease) is a less common type of Dementia. It occurs when the damage to the brain cells occurs only in the frontal lobes of the brain, found behind the forehead. This part of the brain deals with behaviour, problem-solving, planning and the control of emotions. An area of usually the left frontal lobe also controls speech. Unlike other types of Dementia, memory is not normally affected.

It is important not to make assumptions about mental capacity.

In the early stages of Dementia people are often able to, either independently or with support:

- Be involved in care and support processes;

- Provide an insight into their needs;

- Make decisions about care or treatment;

- Decide how best to manage risk;

- Set their own goals and outcomes.

Any lack of mental capacity must be determined by completing a mental capacity assessment.

If capacity is present, the person should be supported to be involved in care or support planning and making their own decisions. They should also be encouraged to think about the ways that their views and wishes can be promoted in the future, for example whether they wish to make an Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment or appoint a Lasting Power of Attorney.

If capacity is lacking the principles of the Mental Capacity Act should be applied to ensure that any decisions made are in their Best Interests.

See: Mental Capacity

A person with Dementia will find it harder to carry out activities of daily living as their condition progresses (for example personal care routines, cooking, socialising and taking medication).

This can happen for a range of reasons, including:

- Forgetting how to carry out some/all of the task;

- Forgetting that the task needs to be carried out;

- Losing the skills required to carry out the task adequately or safely;

- Losing the ability to maintain focus when completing the task.

The loss of independence can have a direct impact on the person’s safety, but also on their mood and mental health, for example by causing anxiety, confusion, anger, frustration, fear, isolation, and withdrawal.

Interventions that promote independence should always be considered and should be provided in a timely way to ensure the greatest positive effect.

Depending on the person’s unique needs, the table below sets out some general rules to support effective communication when the person has Dementia.

| Do | Do not | Further information |

|---|---|---|

|

When completing every care and support task, introduce yourself, your role and why you are there |

Expect the person to have remembered you or what you do |

People with Dementia can forget names and faces, or misplace the context in which they recognise a face |

|

If you need to speak to the person about something in particular, spend some time talking about something that interests them first |

Go straight into the main topic |

People with Dementia can feel socially uneasy and find it difficult to start a conversation |

|

Routinely use the person’s name and wait for recognition before speaking to them |

Provide information to the room if it is meant for the person |

People with Dementia can not always realise you are talking to them unless you are explicit |

|

Sit where the person can see you, do not stand over them, do not appear from behind Use a calm tone, smile, use positive body language and be friendly |

Use authoritative body language or verbal tone |

People with Dementia can become anxious, confused, angry, scared or upset by the actions of others |

|

Speak to the person, not a family member or carer Speak to the person as an adult Seek their views and listen to what they have to say, even if it doesn’t appear to make sense |

Talk over the person, ignore them or whisper to others |

People with Dementia can easily feel isolated, ashamed, worthless and devalued by the actions of others |

|

Keep distraction to the minimum from TV, radio and other people in the room |

Proceed regardless of any distraction |

People with Dementia can find it difficult to focus when there are a lot of things happening around them |

|

Summarise key information Be prepared to say something more than once or answer the same question several times |

Expect the person to retain information without support |

People with Dementia can find it hard to retain new information |

|

Use uncomplicated language and break things down Explore alternative communication, e.g., pictures and objects of reference Give time to process information |

Use inaccessible formats to provide information |

People with Dementia can find it hard to understand the meaning and context of communication or misinterpret information |

|

Be reassuring Offer helpful alternatives - would it be easier to show me? Explore alternative communication, e.g., pictures and objects of reference |

Assume to know what the person wants to say Assume a lack of capacity |

People with Dementia can struggle to find the right words or forget what they want to say |

|

Set timeframes to achieve outcomes that are meaningful to the person |

Plan too far ahead |

People with Dementia can sometimes find it hard to understand the concept of the ‘future,’ anticipate future needs and plan ahead |

|

Rephrase something Take a break Change the environment or go for a walk Change the subject for a while |

Exclude the person from the conversation |

People with Dementia can become overwhelmed by information, and this can lead to changes in mood, behaviour and engagement |

|

Accept the person’s reality |

Correct or challenge them as this can cause confusion, anger and anxiety and serves no purpose |

People with Dementia can have a false perception of reality that is very real to them |

Depending on the type of Dementia, as the person’s condition progresses it is likely that they will experience changes to their mood or behaviour. Examples include:

- Increased confusion;

- Periods of distress;

- Periods of joy;

- Fear and anxiety;

- Frustration and anger;

- Physical aggression towards self and others;

- Suspicion and paranoia;

- Isolating behaviour;

- Loss of inhibition;

- ‘Wandering’.

Some of these changes will be physiological, meaning they are a symptom of their condition as it progresses. However, some will not be.

Many behaviour and emotional difficulties are instead related to:

- A loss of independence, choice, and control;

- A loss of physical and cognitive ability;

- A lack of stimulation or increased boredom;

- A lack of verbal communication;

- Misinterpretation of the communication and actions of others.

Behaviour and emotional difficulties that are not a direct symptom of the Dementia condition can often be managed or improved by making positive changes to the person’s environment or nature of support that will help them to:

- Maintain their independence;

- Communicate more effectively;

- Understand and manage the changes that are happening to them.

Where relevant a referral to a communication or behaviour specialist should always be considered and made.

This section provides information about Parkinson’s Disease, along with some tips and strategies for maximising the participation of people with Parkinson’s Disease in care or support planning, risk assessment and everyday decision making and activities.

Parkinson’s Disease is a condition in which brain cells that produce the chemical Dopamine become progressively damaged over many years.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter. It transmits messages from the brain to parts of the body to make things happen (e.g., movement). As Dopamine levels reduce the body behaves differently and it becomes increasingly harder to control.

The three main symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease are:

- Involuntary shaking of parts of the body (also known as tremors);

- Slow movement;

- Stiff and inflexible muscles.

How a person experiences the three main symptoms of the condition will be unique to them.

Involuntary shaking

Involuntary shaking can occur internally as well as externally and can lead to muscle spasms and cramps impacting on sleep, balance, fine motor skills and the ability to regulate body temperature.

Slow movement

Slowed movement refers to slowed physical movement, but also to slowed thought processes, and can include:

- Slowed gross movement of limbs, eyes etc.;

- Slowed reaction times;

- Difficulty concentrating on more than one thing at a time;

- Delays in processing changes in the environment;

- Delays and difficulty finding the right words;

- Delays in making decisions and processing information.

Any muscle in the body can be affected and, as well as causing pain at times stiffness or inflexibility can impact on a person’s ability to:

- Carry out tasks independently (for example dressing, preparing food, or eating);

- Sit down, stand up, walk around, and use stairs;

- Drive and get around in the community;

- Speak loudly and clearly;

- Chew, swallow, and digest food;

- Breathe normally.

Other impacts

Other impacts include:

- Fatigue (from the increased thought processes involved in trying to control the body);

- Depression and anxiety;

- Loss of sense of smell.

Treatment

Although there is currently no cure for Parkinson’s Disease, treatments are available to help reduce the three main symptoms and maintain quality of life for as long as possible. These treatments involve taking a type of medication that the brain responds to in the same way as it would to Dopamine.

The impact of the medication is normally significant in terms of symptom relief. The effect is only temporary though, and medication needs to be taken regularly throughout each day. As medication is wearing off in between doses symptoms can begin to return, meaning a person with Parkinson’s Disease can have good and bad parts of each day.

As the condition progresses, the symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease can get worse, and treatment can reduce in its effectiveness. As a result, it can become increasingly difficult to carry out everyday activities without assistance.

Parkinson’s Disease does not directly cause people to die, but the condition can place great strain on the body and can make some people more vulnerable to serious and life-threatening infections.

The impact of an effective medication regime on a person’s symptoms and independence cannot be underestimated.

Taking medication on time can literally mean the difference between a person being able to carry out tasks independently or being totally reliant on others.

When planning care and support, managers must understand:

- When the person takes their medication;

- Any support the person may need to take their medication;

- How long it takes for their medication to alleviate their symptoms;

- The impact of the medication on their ability to carry out tasks; and

- How long does the medication remain effective for?

This will enable care and support to be provided in a way that will optimise the person’s ability to carry out tasks for themselves.

If a person requires support to take their medication their individual care or support plan should be explicit about the timing of their medication.

If a person requires support with daily tasks, this support should only be provided when they have taken their medication and the initial side effects (which can include involuntary movements and loss of muscle control) have worn off. This normally takes around 30 minutes.

Ross needs to take his medication at 7am. He does not need any support to do this. It normally takes around 30 minutes for the medication to alleviate symptoms so that Ross can get up and move around. At this point Ross is normally able to manage most of his personal care routine independently if he takes his time but needs support to get dressed and clean his teeth. Ross has support at 7.30am each day, in recognition that this is the optimum time for him. The person providing the support establishes from Ross what he needs help with that day and does not get involved in those tasks that he is able to carry out independently.

Jenny needs support to take her medication throughout the day. As the time for her next dose approaches, she tends to experience increased muscle stiffness. If her medication is delayed for whatever reason she can become temporarily immobile, which has a direct impact on her ability to carry out tasks and functions, such as using the toilet or preparing food. Jenny needs to take her medication every 3 hours for maximum effect. However, she regularly only receives support every 4 hours. This means that her symptoms are often unmanaged for around 6 hours of each waking day, during which her dignity is reduced and her dependence on others is increased.

A person with Parkinson’s Disease should be provided with support from a specialist Parkinson’s Nurse, who can help them to understand the condition and manage their symptoms over time.

If someone is not receiving support from a Parkinson’s Nurse, take steps to enable them to access it. The referral to a Parkinson’s Nurse can only normally be made by a health professional, so this may involve contacting the person’s GP or Consultant on their behalf (subject to normal consent rules).

There is no reason why a person with Parkinson’s Disease cannot fully participate in planning and decision-making processes.

The following table demonstrates some of the steps that staff can take to facilitate this:

| Do | Why? |

|---|---|

|

Try to maintain a calm environment and reassure the person about what is going to happen |

A tremor (shake) can worsen when the person is anxious or distressed. |

|

Ask the person how they are feeling and do not make any assumptions or judgements based on their facial expression |

A person may find it difficult to change the expression on their face to match their mood. |

|

Allow the person to finish what they are doing before talking with them. This could be drinking a cup of tea or thinking about a previous question |

A person may find it difficult to concentrate on something if they are already involved in another task. If time is not allowed, they may forget the task they were previously thinking about, and this could lead to e.g., choking. |

|

Reduce distractions |

Environmental distractions affect concentration. |

|

If you need to talk about something, arrange to speak to a person at an optimum time for them, normally between 30 minutes and 2 hours after medication has been taken |

If medication has not taken effect the person may find it difficult to concentrate, and have slowed reaction time to processing information and communicating their views. |

|

Have important conversations in the optimum environment for the person |

Different environments can increase symptoms because the person may not feel at ease. They can also lead to freezing (a sudden inability to move). |

|

Sit where you can hear the person and consider whether they want to write the information down instead of speaking (although take into account their fine motor skills and ability to write at that time) |

If the person has difficulty with the muscles in their throat, they may find it hard to speak clearly or loudly. |

|

Be mindful that the person may become tired and offer to rearrange a conversation or pause for a break. |

Much of the muscle control that happens naturally in most people requires significant thought, which can result in fatigue. |

|

Allow time for the person to consider things and respond. Do not make a judgement about their capacity based on a slow reaction time |

A person can experience delays in processing information and finding the right words. |

This section provides information about profound and multiple learning disability (PMLD), along with some tips and strategies for maximising the participation of people with PMLD in care or support planning, risk assessment and everyday decision making and activities.

The Health and Care Act 2022 requires all health and social care service providers registered with the Care Quality Commission to provide employees with training on autism and learning disabilities appropriate to their role (called Oliver McGowan Training).

The training aims to provide the social care and health workforce with the right skills and knowledge to provide safe, compassionate, and informed care to autistic people and people with a learning disability.

For further information about the training and how to access it see: The Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training on Learning Disability and Autism.

PMLD is a term used when a person has more than one disability, the most significant of which is always a profound learning disability.

A profound learning disability

A person has a profound learning disability when their IQ is below 20 (a normal IQ is 90-110) and they have social or adaptive difficulties.

Social or adaptive difficulties include problems with:

- Communication;

- Social interaction;

- Managing responses to the environment;

- Carrying out everyday tasks (e.g. eating and drinking, personal care);

- Keeping safe and recognising risks.

Due to the severity of their intellectual impairment most people with a profound learning disability will normally require significant levels of support with every aspect of their life.

Other disabilities

To be described as PMLD a person with a profound learning disability must have at least one other disability, although in reality may have several.

Other disabilities that may be present include:

- A physical impairment (e.g. Cerebral Palsy);

- Complex health needs (e.g. Epilepsy, Dysphagia, respiratory problems);

- A sensory or dual sensory impairment;

- Autism;

- High risk behaviours (towards self or others);

- Mental health difficulties.

Other disabilities are often complex, and, because of the severity of their learning disability, the person will normally be reliant on others to help manage any associated symptoms or risks to health and wellbeing.

Due to the complexity of their needs a person with PMLD is likely to be receiving support from a number of professionals or agencies, which could include:

- A social worker;

- A community nurse (including a CPN or specialist learning disability nurse);

- Clinical Psychology;

- Consultant Psychiatry;

- A Physiotherapist;

- A Speech and Language Therapist (SALT);

- A Dietician;

- Occupational Therapy.

It is important that the service establishes which professionals and agencies are involved (or need to be involved) and consults with them appropriately (and in line with confidentiality).

Care and support methods used to manage risk to (or from) a person with PMLD can sometimes be restrictive.

For example:

- Regular or PRN psychotropic medication;

- Restraint; or

- Physical intervention.

The service must work proactively with social care and health professionals to ensure that methods of providing support are always the least restrictive and all deprivations of liberty are lawful.

The involvement of a person with PMLD in their care and support should always be maximised, even if they have been assessed as lacking capacity to make any decisions that may be required.

People with PMLD find it difficult to understand what is being communicated to them and to respond in a way that has meaning to others. Their communication style is likely to be unique and can take months or even years for others to understand and master.

Depending on the person’s unique needs, the table below sets out some general rules to support effective participation when the person has PMLD.

| Step | Further information |

|---|---|

|

Use a communication passport |

Most people with PMLD will have a communication passport. This is a document developed by a Speech and Language Therapist (SALT) following a full communication assessment. It sets out the person’s preferred communication style, explains the best way to provide information to them, the support they may need to understand it and how to maximise their ability to respond in a meaningful way. If there is no communication passport available, consider making a referral to a SALT. |

|

Consult others and use existing information |

Consult with those people who already know the person with PMLD well, as they are a rich source of information. |

|

Build rapport |

Spend time with the person to build rapport. Observe how they communicate with others and observe how others communicate with them. |

|

Representation and support |

Directly involve those people who:

|

|

Observation as communication |

If the person is not receptive to direct interaction and communication, spend time observing them to allow them to communicate indirectly the things they find enjoyable or challenging. |

|

Use preferred communication styles |

Be open to using whatever communication style will work for the person, and do not worry if this seems unorthodox at times. For example:

If the communication style is evidence based and relevant to the person, it is appropriate to use. |

|

Make sure the person is well |

On the day of any planned conversation or activity, make sure that the person is well enough to take part, especially if they have a complex or variable health condition. Reschedule where necessary. |

|

Limit disruption to normal routines |

The person may be reliant on their routines to provide stability to their day, without which they could become overwhelmed or anxious. |

|

Manage the environment |

Find out what is likely to be distracting, or cause anxiety or distress and take steps to avoid these things. |

|

Manage duration |

Try to plan conversations and activities in line with the person's ability to focus and engage. If this is not possible, factor in breaks so the person does not get tired, overwhelmed, anxious, bored, hungry etc. |

Last Updated: April 16, 2024

v78