Mental Capacity

Scope of this chapter

The Mental Capacity Act is an important piece of legislation. It provides a clear legal framework for us to follow when supporting people to make decisions, assessing capacity and making best interest decisions on behalf of an incapacitated person.

This chapter provides an overview of the 5 statutory principles of the Mental Capacity Act, mental capacity assessment and best interest decision-making. It is vital that everyone in the service understands this chapter and how to apply the Act and its principles in practice.

Upholding the statutory principles of the Mental Capacity Act is a core principle and value. This means that it applies to everyone and is always relevant when planning for or providing care and support.

Relevant Regulations

Related Chapters and Guidance

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 Resource and Practice Toolkit is an online resource included in this Handbook. It provides specific and comprehensive guidance about implementing all aspects of the Act.

You should use it whenever you need to, especially if you need to develop your understanding and confidence in applying any of the principles of the Act.

See: The Mental Capacity Act 2005 Resource and Practice Toolkit

Everyday decisions are those that are made routinely and relate to any aspect of daily care, support or treatment. For example:

- How a person should be supported with personal care;

- How routine medication should be provided;

- How food or clothing choices should be made;

- How transfers should be carried out;

- Routine financial matters;

- Routine treatment, such as accessing the GP or dentist.

The principles of the Mental Capacity Act apply for all these decisions, just as much as they do for major decisions, such as deciding where to live.

There are 5 principles (values) that underpin the Mental Capacity Act 2005. These are defined in section 1 of the Act and set out in the table below.

The principles must be clearly applied. If they are not clearly applied any decision that is subsequently made on behalf of a person who lacks capacity will not be lawful.

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

|

1. A person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they lack capacity. |

Every person from the age of 16 has a right to make their own decisions if they have the capacity to do so. Staff must assume that a person has capacity to make a particular decision at a point in time unless it can be established that they do not. |

|

2. A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help him to do so have been taken without success. |

People should be supported to help them make their own decisions. No conclusion should be made that a person lacks capacity to make a decision unless all practicable steps have been taken to try and help them make a decision for themselves. |

|

3. A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he makes an unwise decision. |

A person who makes a decision that others think is unwise should not automatically be labelled as lacking the capacity to make a decision. |

|

4. An act done or decision made, under this Act for or on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done, or made, in his best interests. |

If the person lacks capacity any decision that is made on their behalf, or subsequent action taken must be done using Best Interests, as set out in the Act. |

|

5. Before the act is done, or the decision is made, regard must be had to whether the purpose for which it is needed can be as effectively achieved in a way that is less restrictive of the person's rights and freedom of action. |

As long as the decision or action remains in the person's Best Interests it should be the decision or action that places the least restriction on their basic rights and freedoms. |

Principle 1: A person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they lack capacity.

The purpose of principle 1 is to prevent you from jumping to any conclusions about a person's ability to make the decision, or act for them self on the sole basis of:

- Their age;

- Their appearance;

- Their behaviour;

- A physical or mental health condition; or

- Having been found to lack capacity to make a previous decision.

Put simply, this principle makes it unlawful to assume that someone lacks capacity just because they are old, young, unkempt, intoxicated, have dementia, have schizophrenia etc.

Making an assumption like this is not only unlawful under the Mental Capacity Act 2005, but could also be unlawful discrimination under the Equality Act 2010.

Mental capacity is also 'decision and time specific'. This means decisions about mental capacity are not transferable to other decisions or points in time and should be made in the moment and at the time that each decision needs to be made.

Principle 2: A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help him to do so have been taken without success

Needing support to make a decision is not uncommon - it is something we all do.

You should never assume that a person lacks capacity to make the decision on the basis that they require support.

Support could include:

- Asking for information about the range of choices that are available;

- Asking for help to understand the implications of the different available choices;

- Needing time to digest information and think things through;

- Wanting advice from a professional; or

- Wanting to seek the views of family and friends.

Other people may need support in relation to their communication, for example for information to be presented in an accessible format or for information to be translated.

If someone needs support to make the decision it is important that you take practicable steps to help them access this support (if they are not able to do so independently).

Practicable steps are the things that it is 'possible and appropriate' for you to do to support the person to make the decision.

They include, but are not limited to:

- Making sure that the person has all the relevant information they need to make the decision;

- Where there are a range of choices, making sure that the person knows about them all;

- Explaining or providing information in a way that is easiest for the person to understand;

- Communicating with the person in the way that best works for them;

- Seeking support from others (for example with communication or to obtain specialist information);

- Making the decision at the optimum time (considering things like the person's need for rest, time to think things over and preferred environment);

- Delaying the decision if the person is unwell or experiencing a fluctuation in their capacity; and

- Making sure the person is supported to make choices or express a view.

The steps that are practicable will vary depending on the needs of the person and the urgency of the presenting situation.

If the decision relates to the care and support being provided to them by the service and you are supporting the person at the time that it needs to be made, then it is your responsibility to establish what steps are practicable. Ideally this should be discussed and agreed with the person, but if this is not possible the steps that you take should reflect what is known about the person's need for support when making decisions.

To make a decision about food, Savid needs to be told verbally what the available options are and be given a few minutes to think about them and make his choice.

To make a decision about what to wear, Annie needs to know what the plans are for the day, what the weather is and to look through the items in her wardrobe.

To make a decision about where to go today, Phil needs to see photographs of the different places and be told how he will travel there, how long it will take and who else will be there - particularly if it is one of his friends.

Further guidance can be found in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 Resource and Practice Toolkit.

This includes guidance on all the following:

- Providing relevant information;

- Communicating in an appropriate way;

- Balanced and objective information and advice;

- Location, timing and presence of others;

- Supporting a person in challenging circumstances.

See: Applying Principle 2: Practicable Steps to Support Decision Making

Principle 3: A person is not to be treated as unable to make the decision merely because he makes an unwise decision.

An unwise decision is any decision made by the person that someone else thinks is not the best decision for them.

Everyone has the right to make the decision that they feel is right for them, even if others disagree with it.

The purpose of principle 3 is to prevent you from applying your own values and beliefs (or the values and beliefs of society) to the person's situation and making a judgement about whether the decision they have made is right or wrong.

It is important you recognise that every decision a person makes will be influenced by their:

- Attitudes;

- Beliefs;

- Values; and

- Preferences.

It is not your place (or the place of anyone else) to judge whether:

- A person's attitudes, values, beliefs, or preferences are right or wrong; or

- Whether the decision that a person makes based on them is wise or unwise.

If a person repeatedly makes an unwise decision that puts them at serious risk of harm (including abuse or neglect), or they make an unwise decision that is obviously out of character it could be an indicator that the person may lack capacity.

For guidance about whether to carry out a mental capacity assessment, see section 7. below:

If their decision making means they meet the threshold for a safeguarding concern to be raised, this should be raised.

If you have reason to believe that a person’s decision making has been influenced by another person through coercion or control, it may also be appropriate to raise a safeguarding concern to the local authority or contact them to discuss the matter and take professional advice.

For further guidance see:

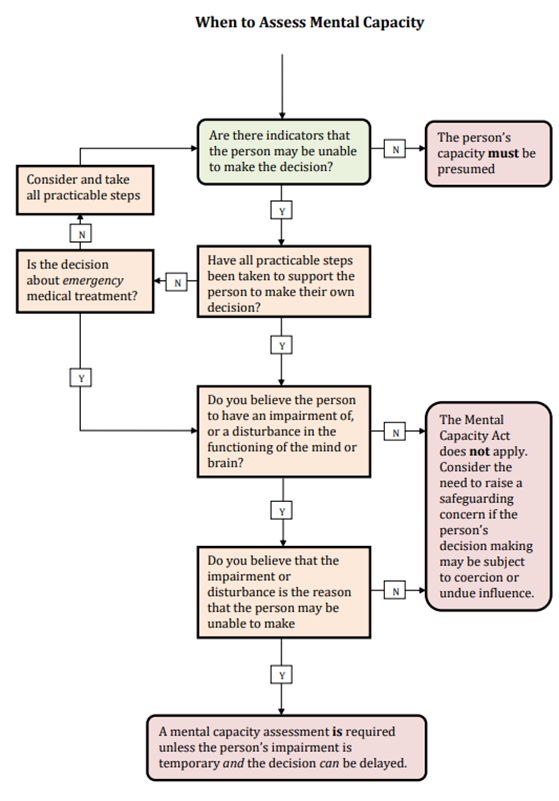

A mental capacity assessment must be carried out when all the following apply:

- There is at least one indicator that the person may not be able to make the decision at the time that it needs to be made; and

- There is evidence that the person has (or may have) an impairment of, or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain; and

- The reason that the person may not be able to make the decision is related to (or may be related to) the impairment in, or disturbance of the functioning of the mind or brain.

Indicators

It does not matter how many of the indicators apply. It can be one or it could be all.

- The person lacks a general understanding of the decision that needs to be made, and why it needs to be made;

- The person lacks a general understanding of the likely consequences of making, or not making the decision;

- The person appears unable to understand, remember and use the information provided to them when making the decision; and

- The person appears unable to, or unable to consistently communicate their decision.

If a person repeatedly makes an unwise decision that puts them at serious risk of harm (including abuse or neglect), or they make an unwise decision that is obviously out of character this could also be an indicator that the person may lack capacity.

Impairment of, or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain

The presence of an impairment or disturbance does not need to be a judgement made by a health professional.

The impairment can be permanent, temporary, diagnosed, or undiagnosed.

| Type of impairment or disturbance | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

|

Permanent |

Any impairment or disturbance that is life-long or on-going |

Dementia, learning disability |

|

Temporary |

Any impairment or disturbance that is short term |

Coma, confusion following an accident |

|

Diagnosed |

An impairment or disturbance caused by a condition that has been formally diagnosed by a suitably qualified medical professional |

A personality disorder, an acquired brain injury |

|

Undiagnosed |

An impairment or disturbance caused by a condition that has either not been diagnosed, is unlikely to be diagnosed or is under investigation |

Drug use |

The purpose of a mental capacity assessment is to confirm whether the person does or does not have the capacity to make the decision that needs to be made.

There are 2 stages to the assessment:

- The diagnostic stage;

- The functional test of capacity.

Comprehensive guidance on carrying out both stages of a mental capacity assessment can be found in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 Resource and Practice Toolkit.

Stage 1: The Presence of an Impairment or Disturbance

Stage 2: The Functional Test of Capacity

The toolkit also provides guidance on deciding the outcome.

Deciding the outcome of the Mental Capacity Assessment and Next Steps

Assessing capacity

The same statutory principles and 2 stage test applies for every assessment of mental capacity. However, as a provider service assessing a person's capacity to decide about, or consent to everyday care and support we are not expected to carry out the same depth of assessment as a professional assessing a person's capacity to make a specific or complex decision.

Recording the outcome of the assessment

Any assessment of capacity that is carried out through the course of providing routine care and support does not have to be formally recorded. However, it should be if any of the following applies:

- It is the first time that the person's capacity has been assessed to make a decision of that kind;

- The person's capacity has changed; or

- The person assessing capacity is concerned about the implications of the decision that the person has made (or not made).

Principle 4: An act done or decision made, under this Act for or on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done, or made, in his best interests.

Principle 4 is also known as the ‘Best Interests Principle’.

The Best Interests Principle is a process for decision making on behalf of a person who lacks capacity to make the decision for themselves. As such, it only applies after a mental capacity assessment has been carried out and reached this conclusion.

Decisions made that do not follow the process are not lawful.

The decision maker is a legal term and describes the person responsible for following the process set out in the Best Interests Principle and making the decision.

Who acts as the decision maker is normally determined by the nature of the decision to be made.

If the decision relates to routine care and support and you are supporting the person at the time that a decision must be made, you will normally be the decision maker. Depending on the potential consequences and risk associated with the decision to be made, a manager may assume the role or support you to make the decision.

If the person has a Lasting Power of Attorney or Deputy, they may be the legal decision maker. This will depend on the specific powers they have been given. If a Lasting Power of Attorney or Deputy exists, the individual care or support plan should set out the decisions that they are responsible for making. If a Lasting Power of Attorney or Deputy has the power to make a particular decision, they must do so and cannot ask anyone else to do it for them.

For all other decisions, a professional will normally assume the role. This is often a social worker or a health professional. In these situations, you may still be asked to provide an opinion about what decision should ultimately be made, and why you think this. Your views will then be taken into account by the decision maker, along with all other evidence and opinion gathered.

It is a legal requirement to involve the person in the decision-making process. They lack the capacity to make the decision but will likely still have a view about what they would or would not like to happen.

If it is not possible to involve the person directly, an advocate or other representation should be considered. Any relevant wishes and views (past or present) expressed by the person should be ascertained and fully regarded.

Further guidance about involving the person in decision-making can be found in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 Resource and Practice Toolkit.

There is clear guidance on all aspects of best interest process in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 Resource and Practice Toolkit.

On the first occasion that a decision about routine care and support needs to be made, the same process should be followed as for a major or specific decision.

A clear record of the decision and the process followed should be kept. This evidences that the best interest process has been followed and the decision is legal.

The process of implementing the decision into the provision of the relevant care and support should be clearly recorded in the person’s individual care or support plan.

Everyone should then follow the process set out in the plan. There is no need to repeat the best interest process or review it unless the circumstances in section 10. Below apply.

Principle 5: Before the act is done, or the decision is made, regard must be had to whether the purpose for which it is needed can be as effectively achieved in a way that is less restrictive of the person's rights and freedom of action.

Principle 5 relates to basic Human Rights. There are 12 rights set out in the Human Rights Act 1998.

For further information about the different rights, see Equality and Human Rights Commission: The Human Rights Act

Principle 5 requires that decision makers consider whether the decision being made (or the way that it will be carried out) could be a breach of the person's Human Rights.

Human Rights that everyday decisions about care and support are most at risk of breaching are:

Article 5: The right to liberty and security (this includes deprivation of liberty)

Article 8: Respect for private and family life, home and correspondence (this includes contact with others and relationships)

Article 9: Freedom of thought, belief and religion

Article 10: Freedom of expression

Article 12: Right to marry and start a family

If there is a danger that a Human Right may be breached, the decision (and the way that it will be carried out) must be authorised by a court or through another relevant legal process/framework.

Note: You should never implement a decision into practice if doing so will breach Human Rights and legal authority to do so has not been given.

If the service can complete the legal process, for example the DoLS process, then it should do so. If not, advice from the local authority safeguarding team (or allocated social worker if the person has one) should be sought.

For information and guidance about deprivation of liberty see:

Recognising a Deprivation of Liberty

A review of the person's mental capacity to make a particular decision should be carried out at each review of their individual care or support plan and whenever either of the following applies:

- A person assessed as being able to make their own decision starts to act in a way that may suggest they are no longer able to do so;

- A person assessed as lacking capacity to make their own decision behaves in a way, or learns a new skill that indicates they may now be able to do so.

This means that if neither 1. or 2. above apply, it is not necessary to review a person’s mental capacity every time that the care or support in question is carried out.

Shortly after the decision has been implemented you should review and record the impact of it on the person. If any of the following applies take steps to review the decision and/or the way in which it is being implemented:

- The anticipated benefits have not arisen; or

- There have been negative impacts that were not anticipated; or

- The impact has been more negative than anticipated.

From then on, the decision should be reviewed at the same time that mental capacity is reviewed or whenever any of the following applies:

- Any of the circumstances upon which the decision was made have changed;

- The person has expressed a different view to those originally expressed.

Mental Capacity Act training is mandatory, and all staff and managers should attend training as part of their induction, and then routinely to refresh knowledge and skills.

Last Updated: September 12, 2022

v42